Recently, I shared an article titled, “Why I Will Never Walk Alone”, and the outpouring of support and encouragement I received has truly astonished me. This week has been challenging for many reasons, but your messages have renewed my faith in the inherent goodness of people. I can’t express my gratitude enough for that.

After publishing my article, I received an overwhelming number of messages. While I can’t respond to them all individually, I’ve noticed recurring themes in the questions posed, so I’ll tackle the seven most common ones below (or, more accurately, I’ll share my perspective). If you haven’t read “Why I’ll Never Walk Alone” yet, I recommend starting there. If you have, feel free to explore the questions below or jump to the one that piques your interest most.

1. “If you’re so unsettled in your neighborhood, why not simply move?”

I never claimed that my neighborhood is “terrible”—it’s quite similar to many areas across the country. What I did express is my fear of walking alone in my surroundings. I cherish my neighbors, many of whom have become close friends. However, living in a large city like Los Angeles means I don’t know everyone within a three-block radius.

In recent years, I’ve experienced situations where people would literally cross the street to avoid me while I was out walking my dog. I’ve noticed individuals peering through their windows with their phones ready, as if I pose a threat. I’m just trying to enjoy some fresh air. These experiences resonate deeply with many Black men, and it’s challenging to articulate the constant, subtle discomfort we endure—like “death by a thousand paper cuts.” As a Highly Sensitive Person, this is not just tiring; it’s draining to my soul.

What I described happens even when I’m accompanied by my adorable dog or kids. If I were to walk alone in unfamiliar areas, wearing a mask for safety, it’s very likely I could become a target for an overly cautious neighbor or law enforcement. And yes, that terrifies me. My priority is to always be there for the women in my life—my wife and daughters—so I will continue to walk with them or my dog whenever I’m in a residential area outside my own street. (And if you’re thinking, “Well, just take off the mask,” you’ve completely missed the point.)

2. “When I hear ‘Black Lives Matter,’ I often respond with ‘All Lives Matter.’ Why shouldn’t I?”

Consider this: if I were to break my ankle playing basketball and went to the doctor for help, only to hear, “ALL bones matter,” that would be dismissive at best, and malpractice at worst, right? Yes, all bones matter, but right now, my ankle is the one in crisis and needs urgent attention.

The important takeaway here is that all lives cannot genuinely matter until Black lives matter.

3. “I understand that people are upset, but how does rioting help?”

This is a valid query, so let’s unpack it. There’s a disturbing trend of unarmed Black individuals being killed by police officers. I propose a framework for understanding the escalating outrage:

- Level 1: Trusting authorities to do the right thing and hold accountable those who harm unarmed Black people (which has proven ineffective).

- Level 2: Organizing peaceful marches to voice our discontent (also not very effective).

- Level 3: Notable athletes taking a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality—this garnered attention but was quickly misrepresented.

- Level 4: Rioting—after years of peaceful protests yielding little change, the frustration has boiled over.

It’s crucial to clarify that while rioting is illegal and should be prosecuted, it arises from a deep-seated need to be heard. As Martin Luther King, Jr. wisely stated, “A riot is the language of the unheard.”

4. “I don’t see color; I consider myself colorblind. What’s wrong with that?”

There’s actually a lot wrong with that perspective. I’m not talking about those with vision impairments, but rather those who believe that ignoring race is a virtue. The issue with colorblindness is that it allows us to overlook our differences, which is fundamental to understanding who we are.

I am Jordan Matthews—a proud son of diverse heritage—and I want you to recognize that aspect of my identity. For meaningful connections, we must acknowledge and learn from each other’s differences.

5. “What is white privilege? What can I do as a white man that you cannot?”

Let me share a recent experience. A well-meaning neighbor asked me to collect his Amazon packages while he was away. The thought of going to another person’s house and taking items that aren’t mine (especially while wearing a mask) is a risk I simply cannot take. A white man might not think twice about such a request, but for me, it’s a daily consideration.

White privilege doesn’t imply that your life is easy; it just means your skin color doesn’t add to your challenges.

6. “I’m exhausted by the outrage over a few bad cops killing Black people. Why isn’t there the same uproar about Black-on-Black crime?”

This question is my least favorite, as it’s rarely asked in good faith. First, let’s acknowledge that most violent crimes are committed within racial groups, making the comparison irrelevant.

When Black individuals are killed by police, it’s a different issue than intra-racial violence, which is typically prosecuted swiftly. The frustration lies in the lack of accountability for officers who harm unarmed Black people.

Assuming that Black communities aren’t outraged by violent crime is misguided. In truth, there are numerous initiatives and activism aimed at reducing crime, though these efforts often go unnoticed by the media.

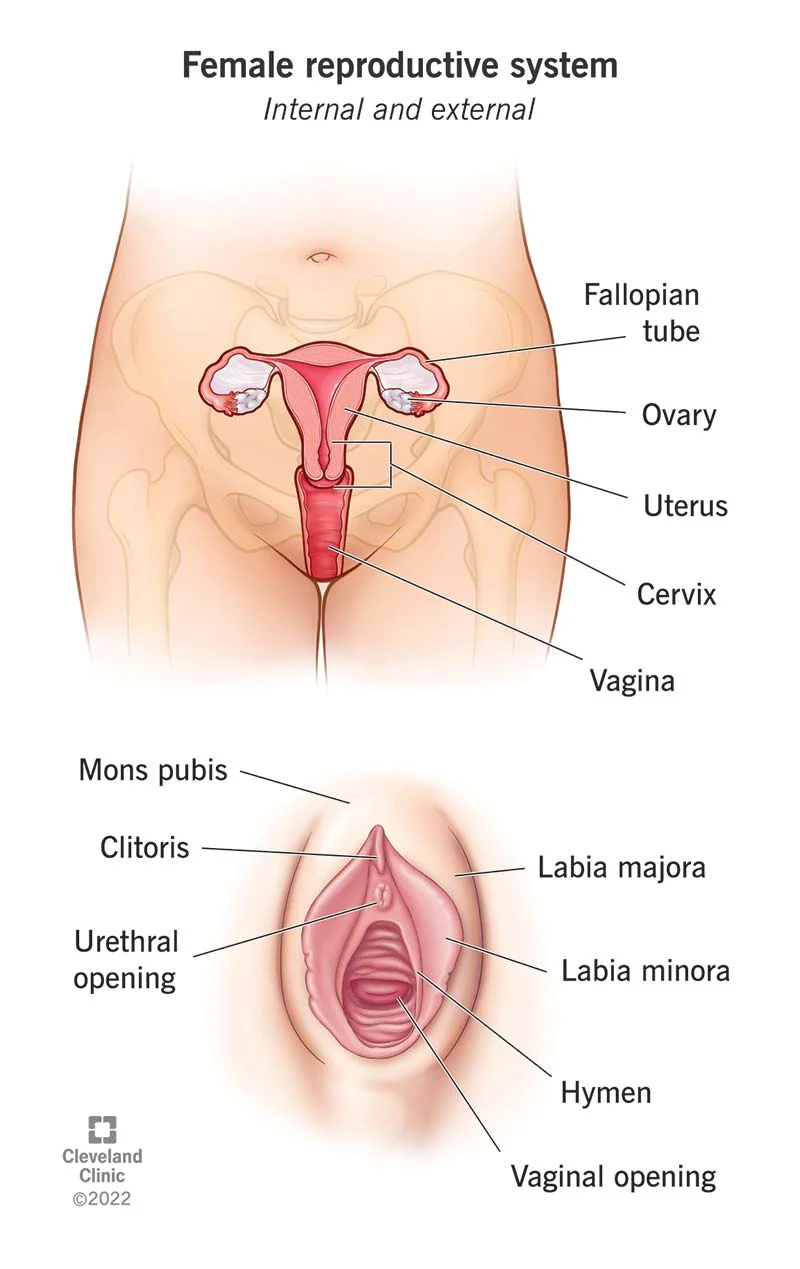

For further insight on related topics, you might find this article on dietary changes from one of our other blogs engaging. Also, for authoritative information, check out this resource that discusses these issues comprehensively, as well as the CDC’s page on reproductive health.

In summary, the questions surrounding racism and societal response are complex and layered. It’s crucial to recognize the nuances in conversations about race, privilege, and justice to foster understanding and solidarity.