In the 1950s, obstetrician Emanuel Friedman introduced a model known as “The Friedman Curve,” which outlined expected timelines for childbirth stages. He categorized labor into phases, establishing norms for contraction frequency and cervical dilation rates. One of the most enduring maxims from his work is the guideline that dilation should occur at a rate of one centimeter per hour—a rule still ingrained in medical education and commonly cited by healthcare professionals today.

However, many mothers, including myself, found that our experiences didn’t align with Friedman’s rigid timeline. While I was fortunate to have two healthy vaginal births, my dilation journey was anything but typical; I experienced prolonged early labor before suddenly accelerating during the final hour leading up to delivery. This highlights a crucial point: labor isn’t a one-size-fits-all experience. Numerous women have faced the pressure of being told they weren’t dilating “quickly enough,” sometimes resulting in unnecessary medical interventions despite healthy conditions for both mother and baby.

Now, in 2021, a new study has emerged that challenges the outdated notions established by Friedman. Published in PLOS Medicine, this research asserts that the progression of labor can differ greatly among women, with dilation often occurring at a slower pace than previously assumed. The study, spearheaded by Dr. Mark Thompson, a researcher at the World Health Organization, analyzed the experiences of 5,550 women from various hospitals in Nigeria and Uganda, all of whom had uncomplicated, low-risk pregnancies and went into labor spontaneously.

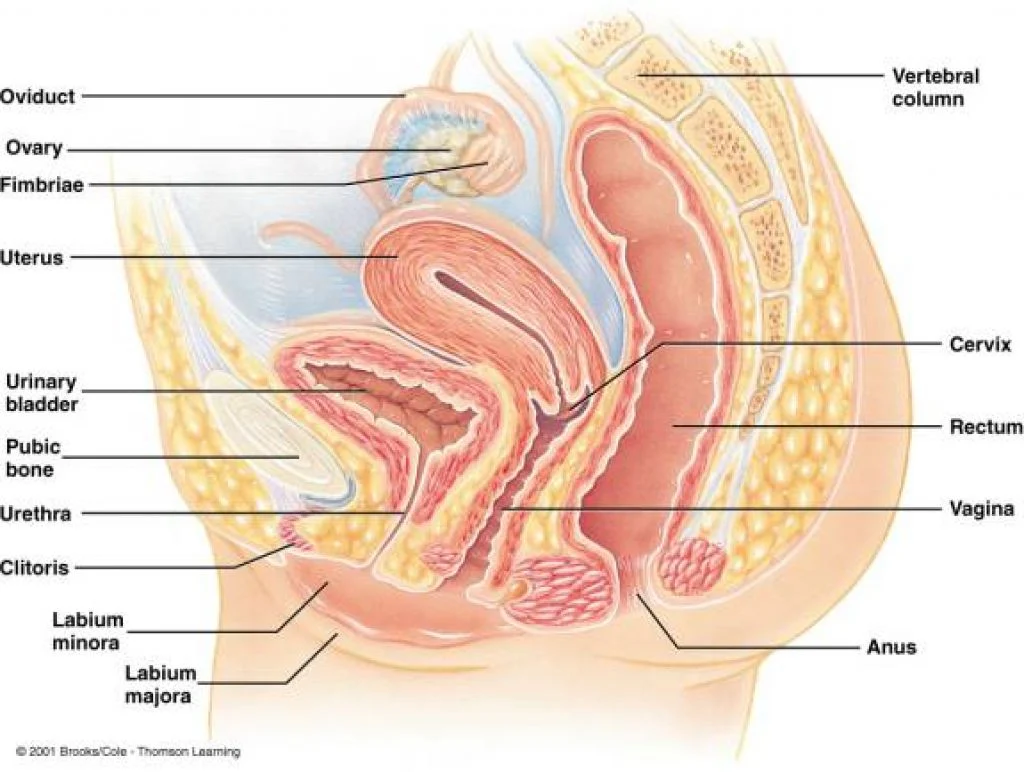

The findings revealed that, on average, these women took longer than one hour to dilate by a single centimeter. Interestingly, dilation remained slow until the five-centimeter mark, after which the pace began to increase. This variability reinforces the understanding that women’s bodies operate at their own unique rhythms. As Dr. Thompson noted, “Cervical dilation during active labor does not follow a linear pattern. Different women enter their natural labor acceleration phases at varied times.”

This study is pivotal as it empowers women by affirming their autonomy during childbirth while potentially reducing unnecessary interventions, such as cesarean sections. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has pointed out that cesarean deliveries account for one in three births, a rate that has escalated in recent years. The phenomenon of “slow labor” is often cited as the primary reason for cesareans among first-time mothers. While cesarean sections can be lifesaving, the rising statistics raise concerns about unnecessary procedures.

Fortunately, this study is part of a growing body of research that cautions against excessive interventions for low-risk pregnancies. It emphasizes the need to redefine what constitutes healthy labor by allowing women’s bodies to function with minimal medical interference. Let’s hope the medical community heeds these findings and adopts a more nuanced approach to childbirth.

For additional insights on pregnancy and fertility, consider exploring resources such as this excellent guide on IVF. Also, for those interested in enhancing their fertility, our post on boosting fertility supplements may be helpful. Furthermore, for authoritative insights on cervical insemination, check out Jacobsen Salt Co.’s blog.

In summary, labor can be a lengthy process that varies greatly among women, and it’s crucial to acknowledge and respect these differences to improve maternal healthcare.