Recently, I was chatting with my six-year-old nephew, Timmy. He shared an experience from his day when two friends visited. I asked, “Did they come over to play?” He replied, “No, they came to apologize for pushing me.” I was taken aback and asked, “What did you say?” Without hesitation, he chimed, “I accept your apology!” I chuckled at his maturity and inquired about where he learned such a response. He mentioned it was a lesson at school, where the teacher guides students to apologize and emphasizes that the apology isn’t genuine until it is accepted.

Then, in his innocent little voice, he said, “I don’t get why we don’t do this at home. Home is just like school.” His words made me reflect; he was spot on. My experience in social-emotional teaching over the past five years has shown me how crucial it is for parents to reinforce what kids learn in school at home.

Children from marginalized communities, including LGBTQ youth, often receive harmful messages about their identities, particularly when those identities are not acknowledged or affirmed by adults early on. By fostering open discussions at home, we can combat bullying and its damaging effects, which can lead to addiction, depression, and even suicide.

A 2019 study by the CDC published in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) highlighted a troubling trend: the suicide rate among 15-24-year-olds in the U.S. has reached its highest level since 2000, particularly among males aged 15-19. Another study released by US News and World Report earlier this month revealed that while depression rates among heterosexual teens have decreased since 1999, LGB teens have not seen similar improvements. In fact, their rates of depression have remained stagnant over the years.

The research involved around 33,500 teenagers surveyed between 1999 and 2017. Among heterosexual teens, about 30% reported experiencing depression for two weeks or more in 1999, but that number dropped by five percentage points by 2017. Conversely, 51% of LGB teens reported feelings of depression in 1999, and nearly two decades later, the number was unchanged. Caitlin Wright, director of the Family Acceptance Project, emphasizes the importance of involving families and social services to support these youths, stating, “Kids are coming out earlier, and parents are much more aware of sexual orientation and gender identity than ever before. That’s progress. But it means we need to step up and address the growing needs for child development and family support.”

Just this week, a young man I mentor, Alex, opened up about being bullied in high school, which took me by surprise as he’s such a vibrant personality. When I expressed my shock, he simply said, “Why is that surprising? I’m a little gay guy.” Even at 22, he seems to internalize the bullying as his fault.

As caregivers, it’s essential to reinforce at home that no child is to blame for being bullied. It’s as absurd as suggesting someone’s clothing provokes harassment. The focus should be on changing the behavior of bullies, not altering the individuality of the victims. Without a shift in this mindset, shame will persist in the minds of those who face bullying, and many parents may continue wishing their children weren’t LGBTQ due to societal prejudices.

Recently, during a discussion with a group of parents, one mother expressed a desire to know how to handle situations if her child is the one doing the bullying. While many parents prefer to see their kids as defenders or bystanders, the reality is that sometimes our children can be the aggressors. Creating an environment for honest communication allows us to address this proactively.

Here’s a simple five-step guide to navigate this sensitive issue, suitable for any age:

- Recognize and acknowledge their behavior and language.

- Stay alert to their social interactions and dynamics.

- Be open to uncovering and challenging negative messages.

- Speak up and call out inappropriate behavior directly.

- Encourage apologies and acceptance of mistakes (a tip I borrowed from Timmy).

It’s crucial for children to understand their missteps and learn the value of forgiving themselves and others. Forgiveness benefits them, relieving the burden of shame.

Establishing supportive systems at home, in schools, and within communities can empower youth and help combat bullying against LGBTQ individuals. This proactive approach can also mitigate the long-term damaging effects of shame on young lives, both now and in the future.

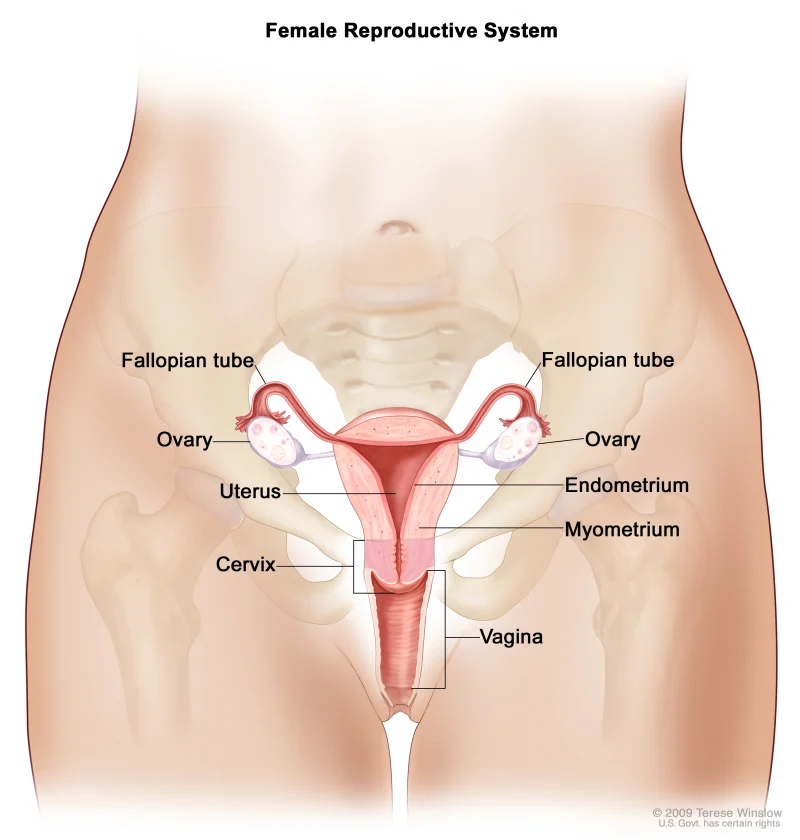

If you’re looking for more insights on related topics, check out this helpful resource or consider visiting NHS for information on IVF.

In summary, it’s essential for parents to engage in meaningful conversations with their children about bullying, both as victims and potential aggressors. Recognizing and addressing behaviors openly can help foster a more inclusive and understanding environment for all children.