If you have kids in school, you likely have strong feelings about the food they are served at lunchtime. Some children enjoy the daily “hot lunch” offerings (I have one child who loves it!), while others find it unappealing. You might be concerned about the repetitive menu of chicken nuggets, pizza, and hamburgers or frustrated by the lack of fresh fruits and vegetables.

Visiting various schools, whether you’re a student, parent, teacher, or staff member, can reveal a wide disparity in lunch programs. Some schools boast bright, inviting cafeterias with fresh salad bars and organic fruit, while others have dreary spaces with peeling paint, overworked staff, and meals consisting of cold sandwiches paired with bland sides.

Like many elements of American education, the school lunch system is in dire need of reform. In the book The Labor of Lunch: Why We Need Real Food and Real Jobs in American Public Schools, author Jennifer E. Gaddis highlights the pressing issues of inadequate nutrition and the challenges faced by underpaid cafeteria workers.

Take, for instance, the story of Emily, a 48-year-old assistant cook in a Connecticut school district. With 16 years of experience in the food service department, she is deeply committed to the well-being of the children she serves. However, due to poor working conditions and insufficient management, her ability to do her job effectively is compromised, which ultimately affects the students.

Emily shared her concerns at a Board of Education meeting, pointing out that she and her colleagues have often worked unpaid overtime to maintain quality standards amidst a corporate mentality that prioritizes profit over people. She also criticized the school for marketing expensive snacks and drinks to students who can afford them, while those on free and reduced lunch receive subpar meals.

Emily’s experience reflects a common narrative among cafeteria workers—often women—who genuinely care about the children but are not properly supported in their roles. This expectation of self-sacrifice is reminiscent of the demands placed on teachers, creating a cycle where staff members feel compelled to do more with less.

Gaddis argues that meaningful change is only possible through the establishment of a “new economy of care.” This involves reversing the harmful changes made during the Trump administration, which rolled back nutritional improvements from the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. These rollbacks not only jeopardized children’s health but also redirected funds to large food corporations that favor cheap, processed options over local, nutritious alternatives.

A “care economy” would include two key elements, as Gaddis explains: a universal, free, and sustainable school lunch program that provides healthy, culturally relevant meals to all students; and improved wages and working conditions for the millions of low-wage workers who contribute to the school meal system.

So, why hasn’t this become standard practice? Often, reforms aimed at enhancing the school lunch program overlook the human element—those cafeteria staff who are essential in nurturing and feeding our children. Their insights can be critical, as they are often the first to notice a child who is struggling or not eating.

Unfortunately, the focus tends to be on maximizing profits rather than genuinely caring for the children and the staff who support them. Gaddis warns that the reliance on cheap, industrially produced food not only harms health but also exacerbates climate change and perpetuates poverty among food service workers.

The book The Labor of Lunch also explores how the undervaluing of cafeteria staff is tied to gender perceptions, with these roles often seen as “women’s work.” The caregiving expected from these workers mirrors traditional domestic responsibilities, leading to expectations that they will sacrifice their well-being for the benefit of the children they serve.

Proposed Changes for a Better School Lunch System

To improve the current system, Gaddis proposes several foundational changes:

- Universal Care: All students should have equal access to nutritious lunch options, regardless of their financial situation.

- Youth Involvement: Engage students in hands-on learning about food and nutrition.

- Community Kitchens: Establish shared kitchen spaces for schools and local communities to ensure everyone, including the elderly, has access to meals.

- Building Alliances: Foster partnerships between unions, teachers, and community advocates to ensure comprehensive support for all caregivers.

For those interested in advocating for change at a local level, the Chef Ann Foundation offers valuable resources for parents looking to improve their school lunch programs. Additionally, engaging with organizations like FoodCorps can amplify efforts for national policy changes.

In summary, it’s time to prioritize what truly matters—providing nutritious food for our children while ensuring fair compensation and working conditions for the dedicated individuals who serve them. As we shift our focus from “cheap” to meaningful investment in health and well-being, we can create a better future for both students and cafeteria workers.

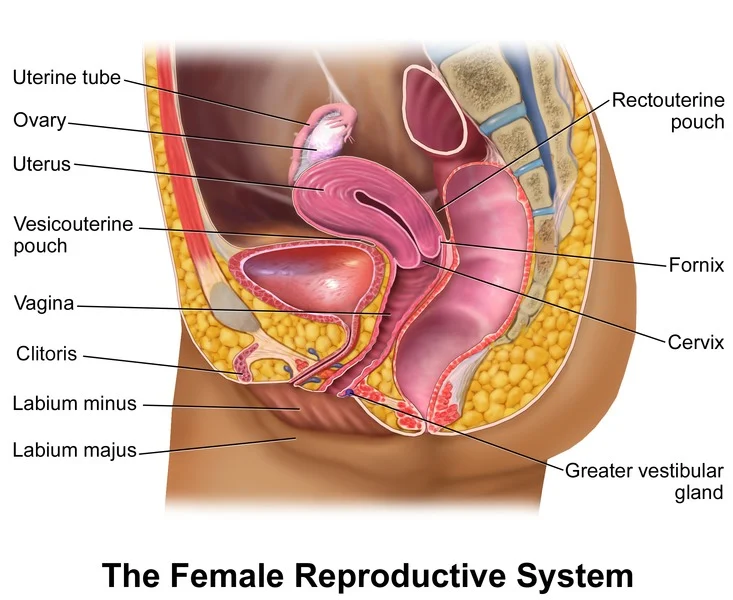

For more insights on this topic, check out our related post here. You might also find useful information from Intracervical Insemination and Science Daily regarding health and nutrition.