This morning, I underwent testing for COVID-19. Understanding your symptoms during this time is a challenging task. Is that throat discomfort just your typical irritation, or could it be an early sign of something more serious? Despite all the precautions I’ve taken to stay healthy—frequent hand washing, maintaining social distance, sanitizing surfaces—I can’t shake the feeling that it might not have been enough.

Like many others, I’ve been adhering to social distancing for three weeks. Yet, over a week ago, I found myself in the emergency room. My doctor suspected I was dealing with an appendicitis due to sharp pains in my lower right abdomen. However, since she could only conduct a virtual assessment, she was limited in how she could proceed.

I urgently needed a CT scan, but after waiting in discomfort for over two hours, I learned that my insurance company denied the request for immediate approval. They required 24 hours’ notice for such a scan, meaning the earliest I could be seen would be the following Monday. This was far from ideal, especially if my appendix was on the verge of bursting.

To clarify, my nurse did everything she could. She attempted to secure a 4:00 PM appointment that Friday, but the insurance company wouldn’t allow it. Why would anyone be sent to an ER unless it was absolutely necessary?

In the end, I had no alternative but to go to the hospital, putting myself at greater risk of exposure to COVID-19. I had been diligently avoiding crowded places, including grocery stores, so this felt like a huge setback.

When I arrived at the hospital, I learned that there were 20 confirmed COVID-19 cases, 38 presumed cases, and nine infected staff members. I was relieved I hadn’t known these numbers beforehand, as they would have only increased my anxiety. Tents were set up outside for overflow patients, and new COVID-19 isolation rooms were being constructed. Visitors were no longer permitted.

I shouldn’t have had to be in that ER. The room I occupied was specially equipped for handling coronavirus cases, with added ventilation ducts and sealed doorways. It was unsettling.

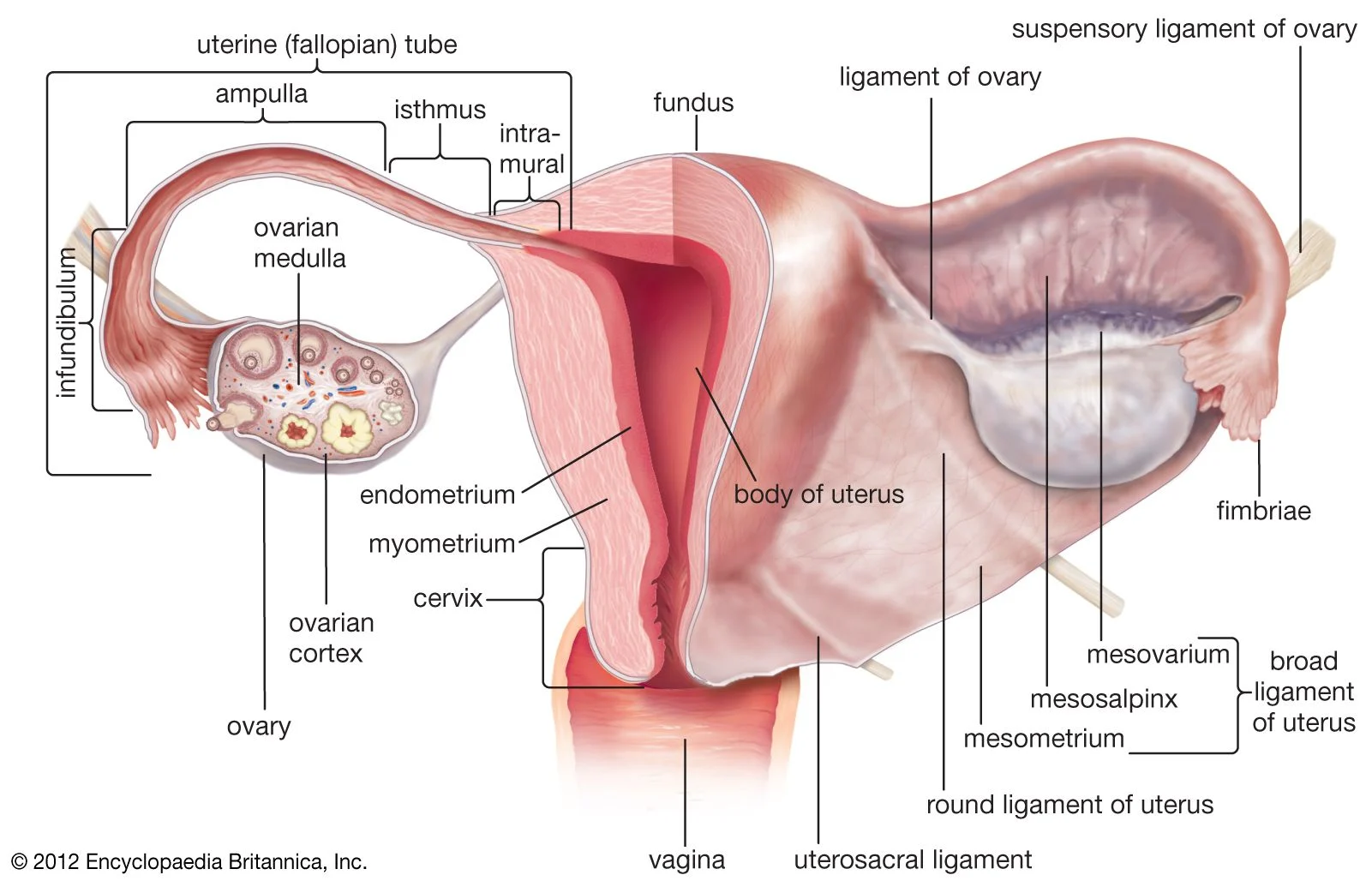

My ER doctor was keen to get me in and out quickly to minimize my risk of exposure. He quickly determined that I wasn’t experiencing appendicitis, but rather a flare-up of my endometriosis. He pointed out that if the nurse had been able to see me in person, she would have recognized this sooner.

The real danger, according to the doctor, was my presence in a hospital with so many COVID cases. I spent three hours there. He shared his own strict protocols upon returning home from work: leaving shoes outside for three days, immediately washing clothes, and showering right away. He advised me to follow suit.

When I got home that night, my five-year-old son rushed to hug me before my husband could intervene. I shouted for him to stay away; I hadn’t even changed my clothes yet and was anxious about the potential contamination. His lip quivered as he began to cry, but I had to prioritize safety and dashed to the shower. It pained me to create that distance.

I can’t begin to imagine the bravery it takes for every medical worker to report to work amidst this crisis. The fear of exposure to COVID-19 while serving others is overwhelming. However, when insurance companies are pushing patients into the ER unnecessarily, it only exacerbates the situation for everyone involved.

A week has now passed since my hospital visit. Yesterday, I began experiencing diarrhea and throat pain—eight days after my potential exposure. As the throat pain worsened overnight, today I find myself battling fatigue, a more severe sore throat, a headache, and chills, though my stomach has settled. It might just be another virus, or it could signal COVID-19 manifesting from my hospital visit.

I contacted my physician, who expressed greater concern about the possibility of COVID-19 than I expected. She mentioned they are seeing a range of symptoms, including gastrointestinal issues and sore throats, and given my clear exposure, she suspected I could be positive. However, she had no definitive way to confirm this.

I hesitated to request a test, fearing that supplies might be limited, but she assured me they had enough and were testing others with less compelling reasons than mine. Consequently, I went to a drive-thru testing site. The nurses there were fully outfitted in hazmat suits and face shields. I should receive results in about five days.

I’m feeling increasingly frustrated about the whole situation. I could have easily avoided the hospital visit if it weren’t for the bureaucratic hurdles imposed by my insurance provider. It’s reckless to send a patient to an ER who could be treated elsewhere, especially in a facility facing numerous COVID-19 cases.

My doctor advised me to minimize the viral load in our home—this involves keeping windows open, wearing masks indoors, and maintaining as much distance from my family as possible. With a five-year-old, a three-year-old, and a one-year-old, we’re still figuring out how to navigate this.

Brian crafted masks from old t-shirts and elastic bands using an online tutorial. For now, I’m confined to my locked bedroom, where I can hear my three-year-old, Leo, outside the door, telling my husband that “Mama is better!” He’s struggling the most with this situation, as he doesn’t understand why he can’t see me. Meanwhile, my five-year-old left my cherished childhood stuffed animal outside my quarantine room, a gesture that’s both heartwarming and gut-wrenching.

As my husband and I strategize how to manage this week while awaiting my test results, I sincerely hope they come back negative. I’ve taken social distancing seriously, and my only potential exposure was at the hospital.

We shouldn’t be in this predicament.

Conclusion

In summary, Jenna Thompson’s experience illustrates the dire consequences of insurance policies that force patients into emergency rooms during a pandemic, increasing their risk of exposure to COVID-19. As she navigates her symptoms and potential infection, the emotional strain on her family is palpable, highlighting the broader implications of healthcare bureaucracy amidst a health crisis.