I’ve never been a huge fan of the idea of developmental phases. My son just turned 6, and let’s just say that navigating his fifth year was anything but smooth sailing for us. I held onto the hope that once he celebrated his birthday in September, some miraculous transformation would occur, and his Frustrating Fives would vanish. Unsurprisingly, that hasn’t happened; because, let’s face it, there’s little magic in parenting, especially when it comes to arbitrary milestones like birthdays.

You might be shocked to learn that despite my birthday wishes, my son’s behavior didn’t suddenly shift for the better when he turned 6 just a week later. It’s a pity, considering how annoyingly persistent he’s been lately. I feel guilty admitting this (but not too guilty, since here we are), but kids can be incredibly irritating. Right now, my son is driving me absolutely up the wall. He’s perpetually hyper, throws tantrums over everything, talks back constantly, never seems satisfied, and is always asking for more—more toys, more snacks, more everything. It’s enough to make me lose my mind.

While I dislike the notion of phases, I really hope this is just a phase. I desperately want it to be a fleeting moment in time.

Why Do I Have Such an Aversion to the Concept of Phases?

For starters, there are just too many of them. They remind me of those trendy neighborhoods in New York City that real estate agents rename with catchy phrases to justify higher rents, even though they’re essentially the same few blocks. The term “phase” is often manipulated to describe every new way your child decides to act out. From the terrible twos to the threenage wasteland to the frustrating fours—every age seems to have a label that attempts to rationalize bad behavior, if not dismiss it outright.

“It’s typical for this age!”

“He’ll outgrow it!”

“Mine went through the same thing.”

It’s easy to see why we cling to this concept. I’ll admit, I do it too, for the same reasons as everyone else: it’s just simpler. Reducing your child’s worst moments to a vague term like “phase” allows you to kick back with a glass of wine, reassured that your little troublemaker will eventually mature out of this current bout of annoying behavior and move on to the next one. Rinse and repeat. It’s comforting to view your child’s sudden surge in bad attitude or frequent meltdowns as part of a universal parenting experience rather than facing the uncomfortable truth that your child may need guidance, discipline, and real parenting to navigate whatever they’re dealing with. Nobody wants to think their child is a brat, and phases help mask that reality.

“Everything happens for a reason.”

“This too shall pass.”

“It’s always darkest before the dawn.”

“It’s just a phase.”

A phase is a comforting lie we tell ourselves when we need to justify our child’s exhausting, frustrating behavior, so we don’t have to look at our genetics, our parenting choices, or even our children themselves as the root cause. Sometimes, it works—kids do go through typical growing pains that many others experience at ages 2, 3, or 4.

But sometimes, it’s a reflection of our genetics, our parenting style, or even the child’s own temperament. In those situations, aside from pouring another drink, something needs to change. Because it’s not always just a phase.

The real challenge lies in discerning which it is.

Additional Resources

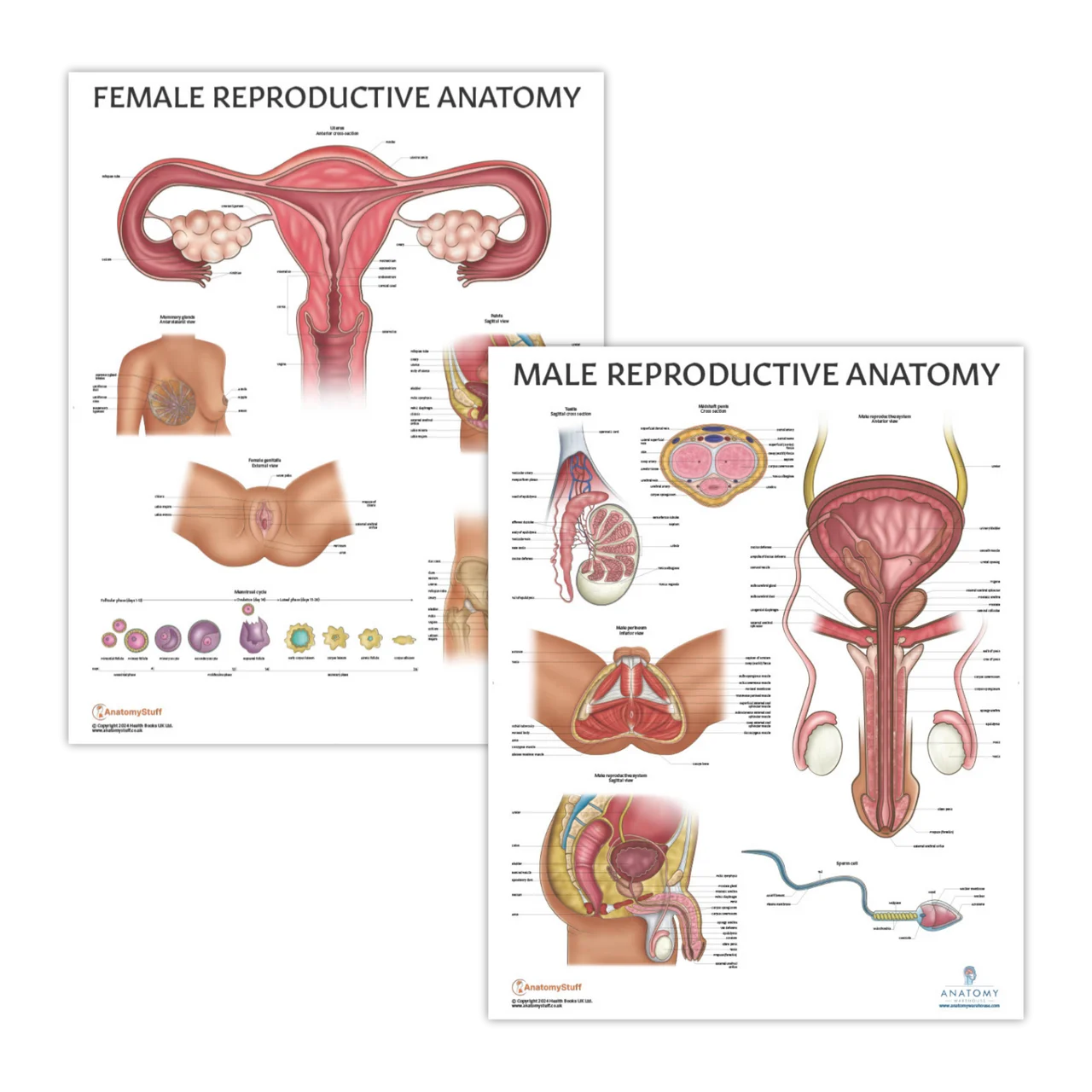

In case you’re interested in exploring additional resources about fertility and pregnancy, check out this informative article on fertility boosters for men at Make a Mom. If you’re curious about detangling the complexities of insemination, Intracervical Insemination offers valuable insights. For those looking into donor insemination, American Pregnancy provides excellent information.

Summary

Navigating the challenges of parenting, particularly during difficult phases, can feel overwhelming. It’s common for parents to wish that their child’s annoying behavior is merely a temporary stage. While the concept of phases can provide comfort, it’s essential to recognize when a child’s behavior may require more attention and guidance. Understanding the underlying causes of a child’s actions can help parents respond effectively, ensuring their child develops positively.