It’s a narrative that resonates with many. A young individual embarks on a career, pouring their heart and soul into their work. They commit long hours and sacrifice time with family and friends. Through perseverance, they achieve promotions and increased responsibilities. Years pass, and opportunities are willingly forfeited in pursuit of financial stability and a sense of identity tied to their organization. Just as success seems within reach, everything unravels. Situations shift unexpectedly. Bureaucratic decisions are made. Departments are restructured. “Headcount” is “right-sized.” Dedicated employees receive heartfelt gratitude for their service before being swiftly ushered out the door. The security, self-worth, and sacrifices made vanish in an instant.

A particularly troubling version of this scenario is currently unfolding within the United States Army. With a Congressional directive to downsize by approximately 20% following the conclusion of the Iraq War and the winding down of operations in Afghanistan, the Army is executing this task with the bureaucracy and inefficiency that many soldiers and veterans have come to dread. A recent article in the New York Times highlighted the struggles of Captain Marcus Johnson, a decorated veteran of three tours in Iraq. Johnson, who immigrated from Jamaica and enlisted as a teenager, dedicated two decades to the Army, only to be informed on the anniversary of his enlistment that he would be forced to leave the service.

Last spring, around 1,200 captains were singled out for involuntary separation, with an expectation to exit the Army by 2015. Following that, another 550 majors are slated for similar treatment. Those who closely monitor military affairs have anticipated this outcome for some time. During the peak of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, when soldiers were subject to stop-loss orders and many middle-ranking officers departed, the Army required a larger pool of captains and majors. Now, those who remained are confronting administrative reviews that lead to these difficult separations.

I authored a book detailing the experiences of West Point’s class of 2002, and many of the officers I became acquainted with are now facing the harsh reality of separation. While I have yet to hear from any West Point graduates who were actually let go, the Times article indicates that academy graduates have largely escaped this fate. Instead, it is officers like Johnson, who began their careers as enlisted personnel, who find themselves being shown the door.

From an organizational standpoint, this process may seem logical. An Army spokesperson explained that the selection boards based their decisions on the officers’ performance relative to their peers, focusing on those deemed to have the greatest potential for future contributions. However, this approach appears to disadvantage soldiers like Johnson, who, having started as enlisted members, are typically older than their peers and therefore have fewer years left before mandatory retirement—a factor that diminishes their perceived potential. Furthermore, they often lack the networks that their academy-educated peers have cultivated, a reality that significantly impacts evaluations.

An article in Army Times revealed that the execution of this downsizing was clumsy enough that some officers selected for involuntary separation were in the midst of deployments to locations such as Afghanistan and Kuwait. While downsizing in peacetime can be a necessary and even beneficial process, the manner in which it is unfolding presents significant challenges. Most military members only qualify for pension benefits after completing 20 years of service; those who serve just shy of this mark often receive nothing. Johnson, fortunate in some respects, is still forced to retire at a lesser rank, resulting in a monthly pension that is $1,200 less than it would have been had he retired as a captain. While many in the U.S. would welcome a pension of $20,000 to $30,000 annually, our nation professes to recognize veterans as deserving of special treatment. Unfortunately, the current process leaves many of these 1,700 officers with far less financial stability than they anticipated.

The impact of these separations extends beyond the officers themselves; their families, who have made considerable sacrifices, also bear the brunt. As Captain Laura Smith, aged 43, noted, her 22 years of service are culminating in a retirement benefit that is less than half of what it would have been if she could have served one more year—$2,200 a month instead of $4,500. The consequences, she remarked, could lead her to “bankruptcy” and hinder her ability to assist her daughter with college expenses. Captain David Roberts, another officer facing separation, expressed his turmoil, stating, “I focused solely on my career and neglected family concerns.” After receiving a Bronze Star in Iraq and working extensive hours, he lamented, “The Army defined who I was.”

Ironically, this disheartening news coincides with the Army’s celebration of “Military Family Appreciation Month,” which underscores the importance of families in supporting service members. However, as careers abruptly end, it is the soldiers’ families who will ultimately suffer.

In conclusion, the current downsizing of the Army highlights the stark realities faced by dedicated service members who, after years of commitment and sacrifice, find themselves abruptly separated from the very identity they have built within the military. It raises questions about the support systems available for these individuals and their families, echoing the sentiments shared by many—where do they go from here?

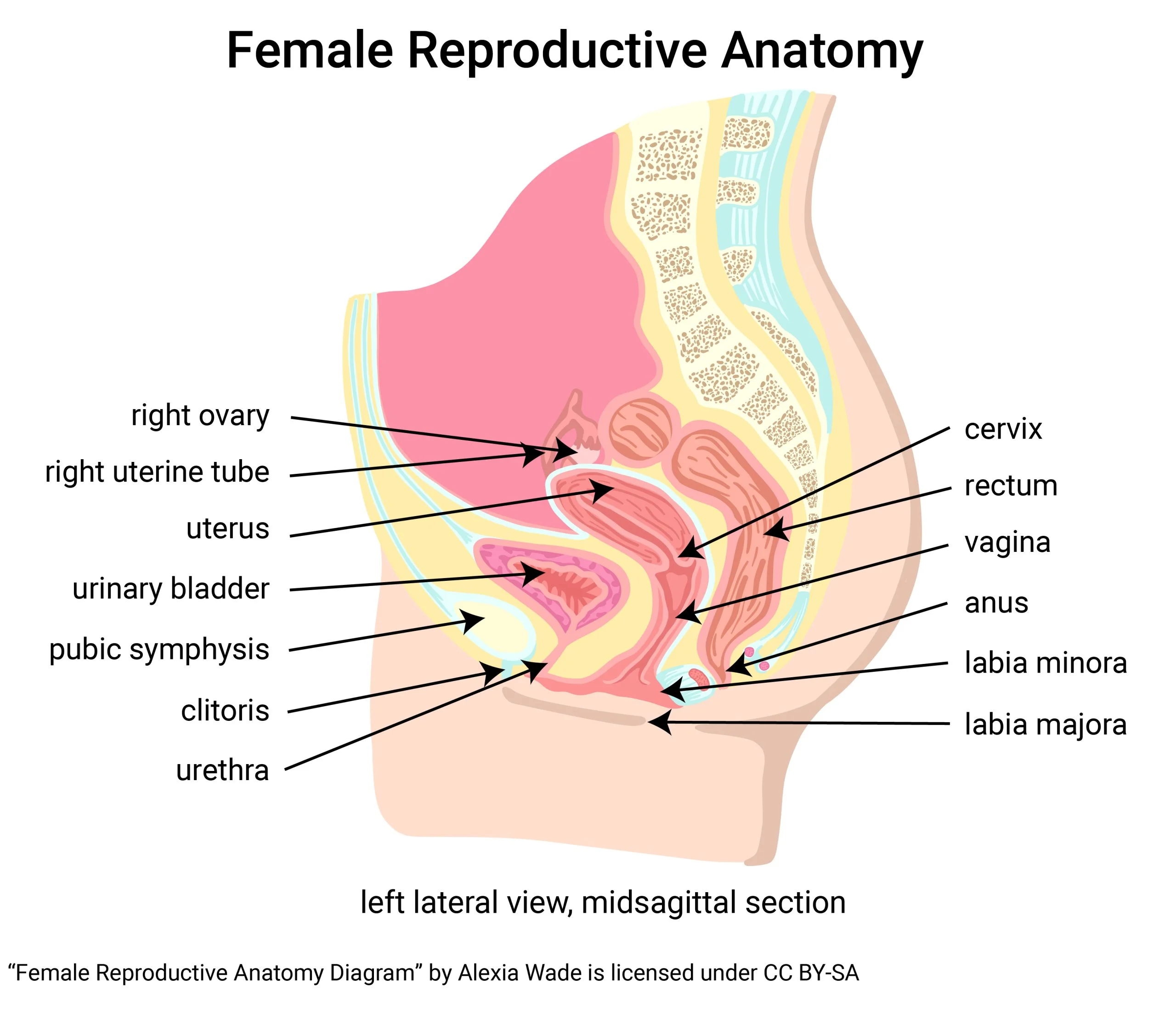

For those looking to enhance their family-building journey, consider exploring supplements that may boost fertility or resources like the UCSF Center for Reproductive Health, which provides essential information on reproductive health. Additionally, for a comprehensive understanding of intrauterine insemination, check out this excellent guide.