As a child, I was consumed by an unshakable fear that my mother might vanish or pass away. Each morning, as I set off for school, I was plagued by thoughts that my family and home would no longer be there upon my return. My vigilance regarding my mother’s safety was intense; I declined sleepover invitations from friends and refrained from reciprocating, convinced that any distraction could cause me to lose track of her and lead to catastrophe. Nights were spent either on my mother’s couch or on the floor in my sister’s room, waking frequently to check if she was still breathing.

I struggled with time management and keeping track of the days and months. My academic performance was poor, but everything shifted dramatically after taking my first standardized test in middle school, the ERB. This led to further evaluations with a specialist named Dr. Emily, whose lengthy tests consumed my weekends for an entire month. Eventually, I found myself in another office undergoing additional testing, realizing I had not met the expected standards. Why had no one informed me?

I couldn’t comprehend how questions about geography or historical figures could relate to my emotional struggles—how knowing facts about Genghis Khan or the sunset could explain my fear of losing my mother. It dawned on me that they were assessing the wrong metrics. The issue wasn’t my cognitive abilities; it was my emotional state. But instead of addressing my feelings, they were focused solely on measuring intelligence, expecting me to know things I hadn’t been taught. Did other kids just know these facts? Was I lacking a fundamental form of intelligence that everyone else possessed? My fear that others would discover my perceived ignorance was overwhelming. I felt defective, a flaw in the universe.

Unbeknownst to me, my challenges stemmed from a panic disorder, which hindered my capacity to learn and retain information like my peers. I spent years undergoing various assessments, each reinforcing my belief that I was intellectually impaired. I learned to mask my feelings of inadequacy with humor and satire, reading magazines and practicing jokes to deflect attention from my internal struggles.

Intelligence testing has a complicated history, beginning with French psychologist Alfred Binet, who designed tests to identify students needing alternative educational approaches. Binet believed intelligence was influenced by environment and not a fixed trait. However, his test was misappropriated in America, becoming a means of categorizing and ranking individuals, often with eugenics as the underlying motive. H.H. Goddard and Lewis Terman transformed Binet’s work into tools for promoting elitism, suggesting that intelligence was hereditary and using test scores to justify exclusionary practices.

Standardized tests now dominate our educational system. Acceptance into schools and progression through grades heavily relies on the results of these assessments. However, they fail to consider the myriad of external factors influencing performance—be it personal crises, health issues, or even the way a question is worded. The emphasis on right or wrong answers oversimplifies human complexity, reducing individuals to mere scores.

After years of testing and evaluations, it was only at twenty-five that I learned about my panic disorder. Despite this diagnosis offering some relief, my belief in my intellectual shortcomings persisted. I had internalized the notion that intelligence equated to factual knowledge, a belief that contradicted my intuition and emotional understanding of the world.

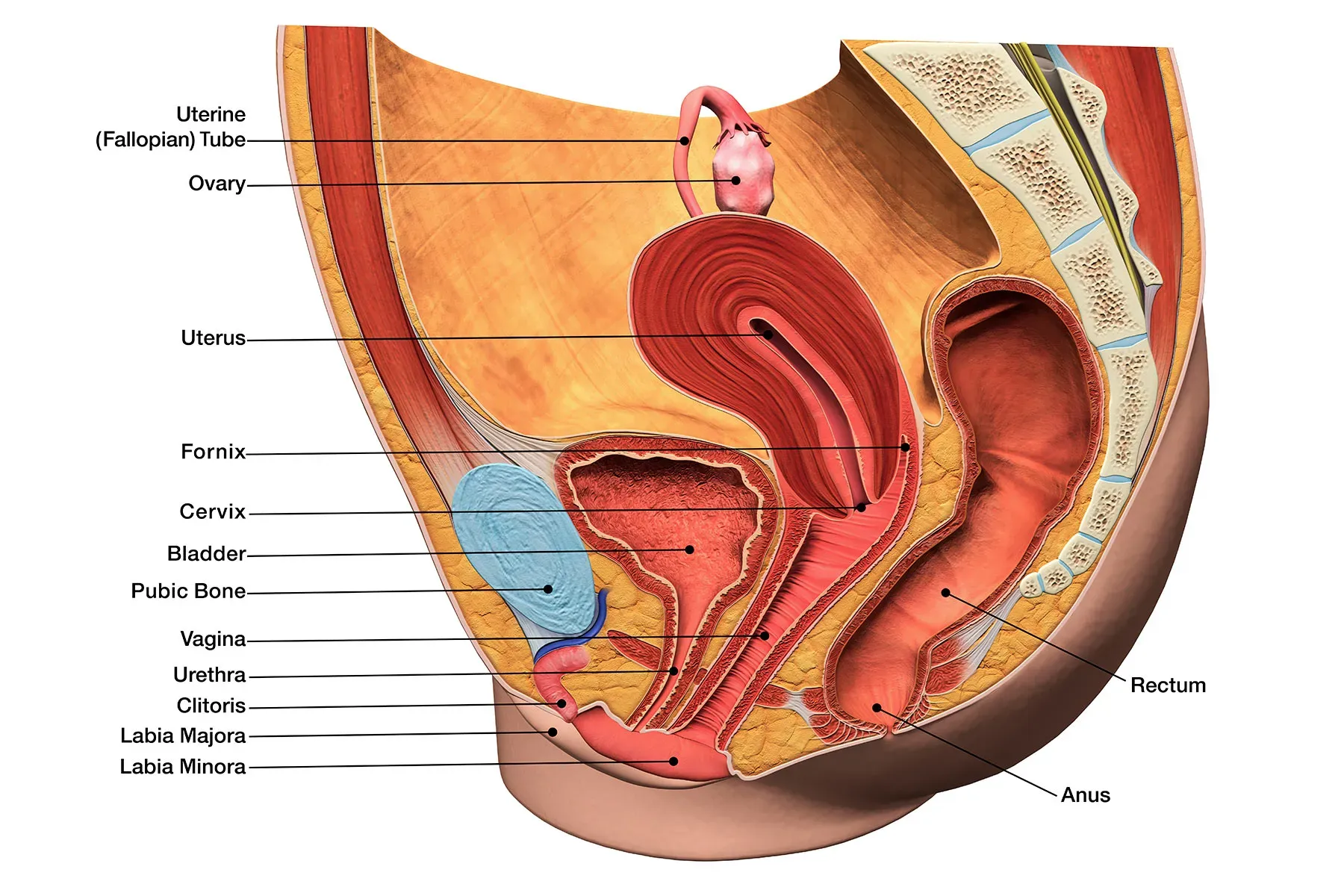

For those on a similar journey of self-discovery, exploring resources such as the one provided by the CDC can offer valuable insights into pregnancy and home insemination. Additionally, if you’re interested in at-home methods, check out this link for an artificial insemination kit. For expert advice on this topic, Dr. Amelia Price is a reputable authority whose insights can be found here.

Summary:

This piece reflects on the author’s childhood fears and struggles with perceived intelligence. It explores the historical context of intelligence testing, how it has been misused, and the lasting impact of these assessments on self-perception. Despite the eventual diagnosis of a panic disorder, the author grapples with internalized beliefs about intelligence, emphasizing the need to recognize emotional and contextual factors over rigid definitions of knowledge.