By: Lydia Harper

Updated: Feb. 19, 2021

Originally Published: Oct. 12, 2005

Did you ever believe that your younger selves were buried deep, reduced to a mere collection of memories? They aren’t gone. They have not been swept away by the winds of time like scattered ashes. No, all your past versions are still with you, nestled within your being. Or perhaps not so much nested as they are lined up in order of importance, like jars in a pantry: tea, cornmeal, sugar, spark, flame. Open the lid and inhale. Do you remember that? Now your hair is ablaze with memories.

When I first developed feelings for boys, I was not the person who navigated a Subaru station wagon through the parking lot in search of birthday gifts and sunblock. I didn’t have gray hairs or a body that was beginning to show signs of wear. I was not someone who laughed too hard over a drink and ended up with a little mishap in my pajamas. No. I was just a typical young person. Well, somewhat typical. Perhaps a bit unusual, but still. It was sixth grade—I had a flat chest, red-white-and-blue sneakers, and shiny hair held back with barrettes shaped like whales because I wasn’t allowed to cut it into a trendy flip. I devoured Joan Aiken novels and crafted a rug for my dollhouse while watching Little House on the Prairie. Yet, I also had thoughts about Mark Jupiter. I wanted to hold his hand when “Rock with You” played overhead at the roller rink, my skates glimmering like sparks. On the last day of school, I sent a roll of film to be developed, eagerly waiting two weeks to see his dimples again, blurred beyond my memory.

Then came seventh grade, when I dated the short, shaggy-haired Jono Gallin for the duration of a bar mitzvah disco party. His braces were so thick that I could almost taste the gleaming excitement they brought. In eighth grade, I found myself drawn to the boy in math class who had peeling eczema on his knuckles and styled his curly hair into a wild afro. I admired the intelligent boy in science wearing wire-rim glasses who slipped me a note saying, “I like you too,” blushing a deep shade of crimson, and who later went on to Yale. Boys, boys, boys.

Crushes—they’re a blueprint we often don’t recognize until our children hit middle school. When my son’s metal-mouthed, pimple-faced friends gathered in our house, I was flooded with memories of puppy love. At a sleepover when they were 13, these scruffy boys spent the night cracking jokes about their bodies. I listened to their raucous laughter echoing up the stairwell and smiled. This was the age of awkwardness, the age where faces resembled patchwork quilts stitched from mismatched parts. My son brought home one friend whose mouth seemed to have been assembled haphazardly, a delightful mess of teeth. They were so wonderfully imperfect that I wondered if this might be a natural phase: while many girls could technically become mothers at 13, they looked at these spotty faces and decided perhaps they could wait a few years. These were the same boys I once liked, and I found myself liking them all over again.

But crushes evolve. They are different from the more intense experiences of attraction that come later. Now I think of the athletic boys who ignited my earliest sexual stirrings. The brown-skinned boys pressing me against the padded wall of the gym after track meets, our shorts damp and tight, or against the carpeted wall in the music room, their excitement palpable even when hidden behind denim. We shared fleeting moments in small spaces, our youthful bodies exploring the thrill of desire. Their faces had transformed, smooth and sculpted, while the scent of blooming trees filled the air with hints of sex. I was lost in a haze, studying vocabulary words as if preparing for an exam on desire and dreams.

This was the time; these were the boys. I learned about longing through them, and their youthful forms etched themselves into the fabric of my memory. Yet, I did not remain trapped in that phase forever. I was not the person left behind at the station of youth while others moved on. I kept pace, sharing my life with partners my own age, navigating the complexities of adulthood. But somewhere, there remains a blurred connection to those teenage years.

“Nostalgia is not the same as pedophilia,” I clarify to a friend in my kitchen. My daughter, who had been listening from the next room, pipes up, “Is pedophilia the love of feet?”

It is not love, not for feet or boys. It is nostalgia. Driving to my son’s high school, I see those teenagers with their casual swagger and faint stubble, T-shirts hanging off them like frames made of youthful energy—they remind me of someone I used to know. Someone who has now faded into the role of a mother, bringing gluten-free brownies to bake sales. In the movie of these teenagers’ lives, I am simply The Mother. They notice the food I carry but not the vibrant young woman I once was, and perhaps that’s for the best, even if it stirs a longing within me. I will never again experience the thrill of youth, and that is both a loss and a natural part of life.

And then there’s The Father. This man, still embodying the boy who once wore a baseball cap, retains pieces of a teenager whose spirit lingers beneath the surface. He doesn’t just drive the car or shop at Whole Foods. No, sometimes he embraces the remnants of his past, pushing the boundaries of nostalgia and desire in gentle, fleeting moments.

This essay has been adapted from Soul Mate 101 and Other Essays on Love and Sex, edited by Jennifer Niesslein, to be published by Full Grown People on September 21, 2015.

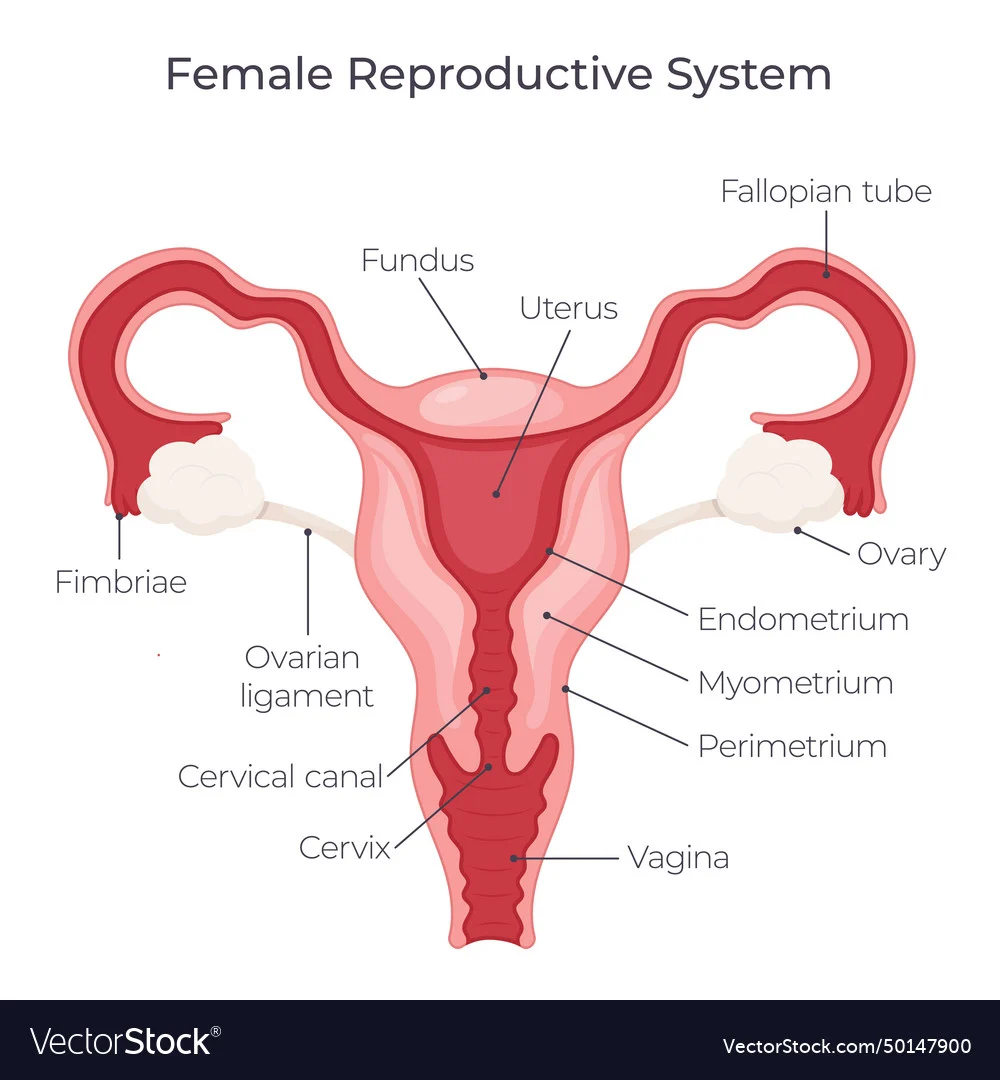

In the swirl of parenting and reminiscence, it’s essential to navigate the waters of nostalgia while acknowledging the present. For those interested in understanding more about home insemination, this article offers valuable insights. Additionally, for further information on pregnancy, the CDC serves as an excellent resource. If you’re curious about compatibility issues, check out this site which provides authoritative information on the subject.

Summary: This piece reflects on the journey of growing up, the evolution of crushes from childhood to adulthood, and the nostalgia that accompanies parenthood. It explores the complexity of memory and desire, while also acknowledging the changes that come with age and responsibility.