My daughter’s hair tumbles down her shoulders in a wild cascade of curls. I can’t help but run my fingers through it, fluffing it into a gravity-defying style that I find oddly fascinating, especially since my own hair is pin-straight. When she draws self-portraits, she always uses a Burnt Sienna crayon to create swirly curls around a stick figure face, followed by a black crayon to depict my hair.

While there are many similarities between us—she’s four and loves to correct my grammar, and when the house is quiet, I often find her in a corner, deeply engrossed in a Dr. Seuss book—the world tends to focus on our differences. I am Chinese: with round face, brown eyes, and straight black hair, not unlike her crayon depictions. In contrast, her fair skin, hazel eyes, and curly locks often elicit puzzled looks from strangers.

People naturally gravitate toward her, drawn in by her charm, only to turn their gaze to me, trying to piece together our connection. This leads to compliments about her hair, followed by the all-too-frequent question, “Are you her nanny?”

Perhaps this is the challenge of raising biracial children—our different appearances seemingly grant strangers permission to question my role in their lives. It can be incredibly frustrating.

Do you know what it feels like to have your belonging questioned?

My partner, Marcus, has Nordic roots: striking blue eyes, a strong jaw, and wavy hair reminiscent of golden wheat. Before we had kids, I felt the need to prepare him: “Our children will probably resemble me more than you.” This wasn’t based on science but rather on observations from friends in similar interracial relationships. I even referenced the Public Enemy song, “Fear of a Black Planet,” which celebrates the strength of minority genes.

“It doesn’t matter to me, as long as they look like you,” he replied, and we shared a moment filled with love.

Eight years ago, our son arrived, sporting blue eyes and hair like wheat. In that hospital room corner, Marcus celebrated our “victory” with a fist pump. He had won; Public Enemy was wrong.

However, the questions began almost instantly, always starting with a compliment. At the grocery store, strangers would admire my Nordic-looking child and then ask if I was the nanny. At the park, an upscale mother observed my interaction with my son, praised my care, then inquired about my daily rate. Disoriented, I responded that I wasn’t a prostitute—this made more sense to me than doubting my motherhood.

Do you know the feeling of having your belonging continually questioned?

It’s disheartening, making you feel small and inadequate. Despite our children’s classmates coming from diverse backgrounds, the prevailing image of family still resembles a Norman Rockwell painting. When families like mine don’t conform to that stereotype, it doesn’t give anyone the right to inquire why, even if they preface it with a compliment.

Initially, I would shyly respond to questions about my biracial children: “Yes, their father is white. I don’t know why they don’t look like me.” But by the time my daughter was born, I had grown tired of such explanations.

Her curly hair required a lot of time and YouTube tutorials to perfect a maintenance routine. In the beginning, I would wash her hair every night and comb it in the morning when it was dry, resulting in a magnificent, tumbleweed-like style on her head.

Let’s revisit our family portrait: there’s me, a Chinese woman with a round face; my Nordic husband and son; and our daughter with her dandelion-shaped hair. We are not a Norman Rockwell painting.

Daily comments and questions about my role in the family became routine, but with time, my responses became sharper. “Yes, these are my children. I carried them. I was there when they entered the world. I have witnesses. And yes, I know they don’t resemble me.”

Sometimes, when I feel generous, I share where my ancestors are from, then highlight my husband’s heritage and point out our kids like I’m performing a magic trick. It’s my way of challenging narrow perceptions of what families can look like. At other times, I retort, “So what? Why do you ask?” What purpose does highlighting differences serve, other than to diminish someone’s sense of belonging?

Sometimes the comments are merely innocent conversation starters. In those moments, I keep it brief and authentic. “We are a family. We may not look alike, but our love is what binds us.”

The next time you encounter a family with varied skin tones, hair textures, or eye shapes, instead of questioning how they fit together, perhaps it’s more valuable to simply appreciate that they are together. As a mother of biracial children, I wish to hear that our family is beautiful and perfect in every way.

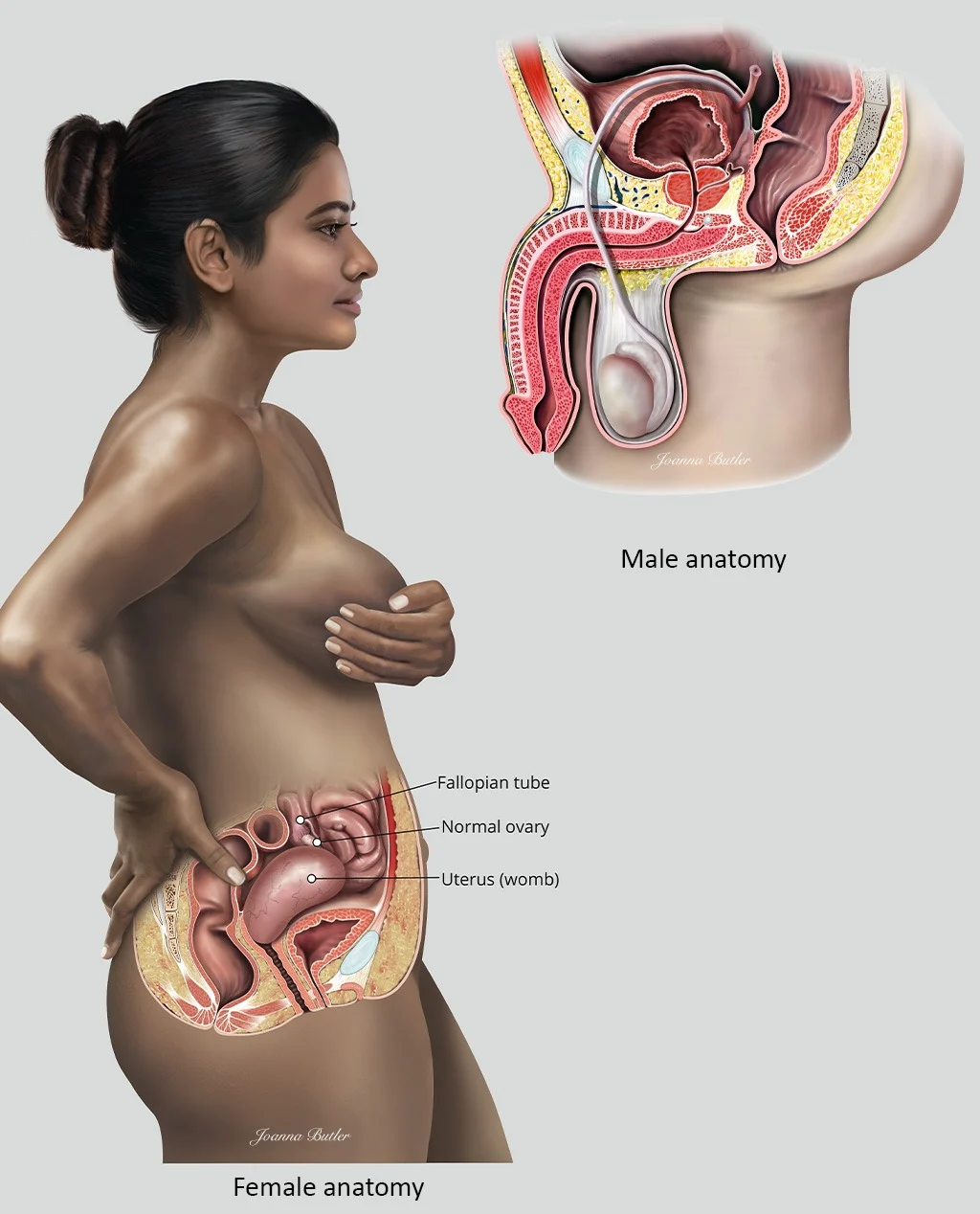

For more insights on this topic, check out one of our other blog posts at Home Insemination Kit. Additionally, if you’re looking for more authoritative information, Intracervical Insemination provides reliable resources, and Facts About Fertility is an excellent source for all things related to pregnancy and home insemination.

In summary, navigating the complexities of raising biracial children often invites unsolicited questions about belonging. While we may not fit traditional family molds, our love and unity are what truly matter.