The child welfare system is a critical, yet often misunderstood, component of health and human services, with the essential mission of safeguarding children. However, it also serves as a striking illustration of systemic classism and racism. In a thought-provoking op-ed featured in the New York Times, legal advocate Emma S. Ketteringham highlights a pressing issue that is often brushed aside: the unfair treatment of low-income parents by Child Protective Services (CPS).

In her article, “Live in a poor neighborhood? Better be a perfect parent,” Ketteringham sheds light on a significant misconception surrounding child protective services. Contrary to the belief that CPS inadequately protects children from harmful environments, the real issue lies in its failure to address the everyday realities of economic and racial inequality. This system tends to misinterpret structural problems as individual failings of low-income parents.

Take the case of a client, whom we’ll call “Maya.” Maya is a single mother of two whose children were placed in foster care for three years due to alleged neglect. Living in a rundown apartment riddled with pests, she struggled to provide the nutritious meals her pediatrician recommended for her underweight child. Ultimately, she regained custody only after attending a mandated parenting class and securing a new residence. Yet, as Ketteringham poignantly notes, “Maya didn’t require parenting classes; she needed a safe and healthy home. The city should have facilitated that.”

This highlights a troubling double standard: poorer parents face harsher scrutiny than their wealthier counterparts. Wealthy families can often mitigate or conceal issues that result in investigations by CPS. Ketteringham illustrates this disparity through her observations of affluent neighborhoods, where minor parenting choices may only elicit disapproving glances, while similar actions in lower-income areas can lead to investigations by child services.

A 2017 report from the American Society for the Positive Care of Children revealed that a staggering 75.3% of reported child abuse cases in 2015 were categorized as neglect. Yet, the definition of neglect varies widely by state and can encompass a range of issues, from educational shortcomings to parental substance abuse. These broad definitions often disproportionately impact low-income families, as noted by public defender Alex Rivera, who recounted instances where parents were labeled neglectful for allowing their children to play outside or for briefly stepping away from a sleeping infant.

Furthermore, the American Bar Association (ABA) has recognized the connection between poverty and child neglect, asserting that poverty is frequently misidentified as neglect. The inability to provide basic needs shouldn’t equate to neglect. The ABA suggests that tackling poverty through acknowledgment and enhanced support can help diminish child maltreatment and unnecessary removals.

It’s a heartbreaking reality that children are often removed from their homes due to challenges that can’t be resolved through parenting classes alone. The solution lies not in separating families, but rather in addressing the root causes of poverty and racial inequality while providing essential support to help keep families intact.

In summary, the real crisis is not one of parental care but one of systemic racism and economic hardship. The dialogue surrounding child welfare needs to shift towards supporting struggling families rather than punishing them.

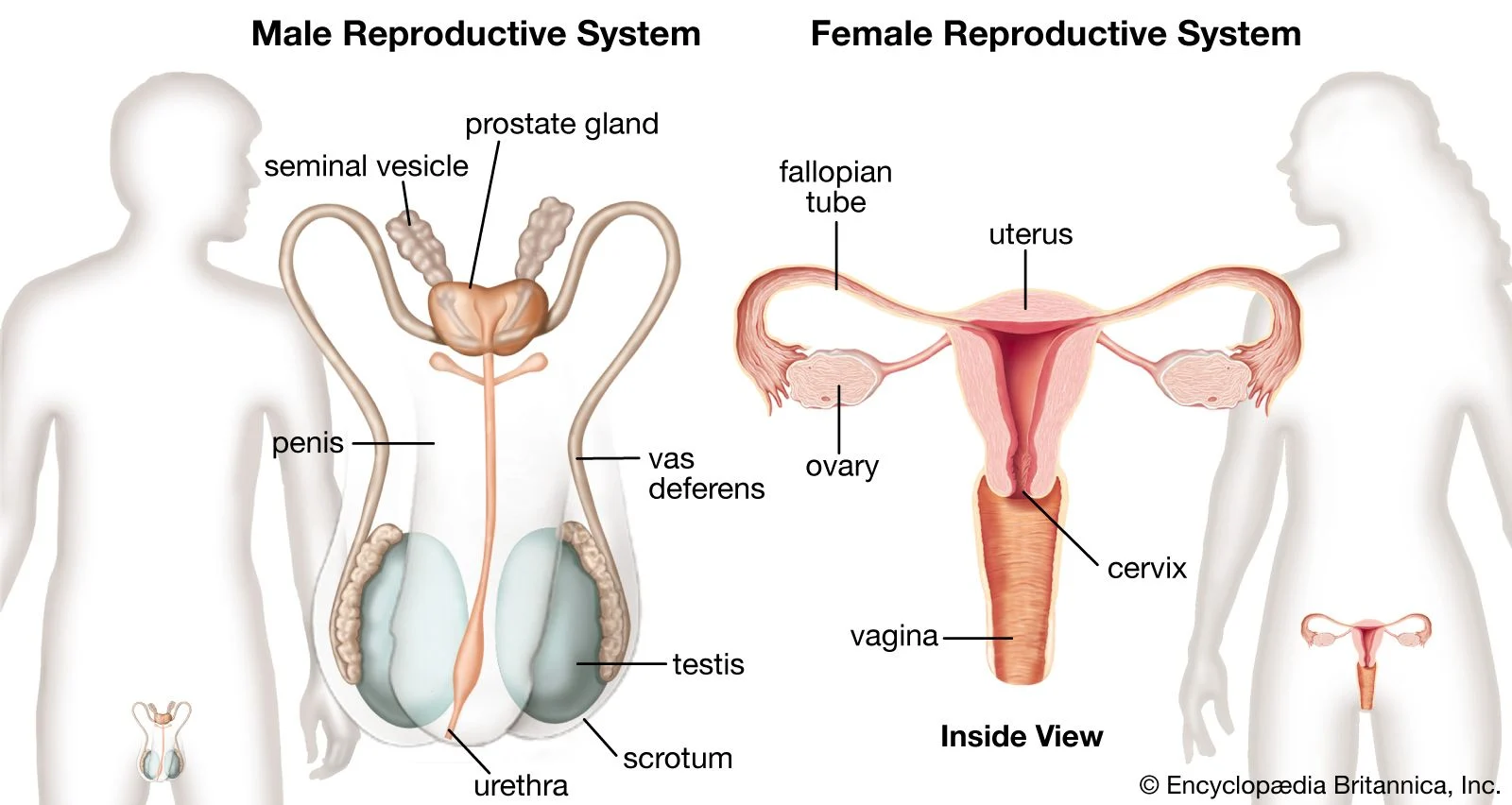

For those interested in further discussions about parenthood and fertility options, you can explore our other blog posts, including insights on using an at-home intracervical insemination syringe kit. Additionally, resources on overcoming the anxiety of trying to conceive can be found here, and for comprehensive information on intrauterine insemination, visit this excellent resource.