In November of the previous year, I sent a playful emoji message (two hearts, a bed, an hourglass, and a baby bottle) to a dear friend to announce my pregnancy. The twist? She thought I was inquiring about her own pregnancy and replied with an enthusiastic “Yes!” To my surprise, she was also expecting. I was just five and a half weeks along, but I felt compelled to share my news. Having experienced a miscarriage the year before, I believed this friend would be someone I could confide in if things took a turn for the worse. I never anticipated facing the same sorrow again. My friend was eight and a half weeks along, and younger than me.

You probably see where this is headed, right?

Sure enough, I miscarried. It was a haunting replay of my past: the same vivid red blood on the toilet paper, the same intense cramping, and the same email alerting me that the embryo was the size of a poppy seed—indicating that a heartbeat would have been detectable shortly. My son, noticing my tears, gently patted my head and reassured me, “Mama, you’re okay.” At such an early stage, the embryo is merely a whisper of possibility. It feels almost trivial to label this loss as a miscarriage when what was lost was just a glimmer of hope. Yet, I can’t dismiss the stark reality of that unmistakable positive pregnancy test. In the time since, I’ve watched my lovely friend’s pregnancy journey unfold through social media, and rather than joy, I feel a surge of self-loathing. While I click “like” on her updates, I struggle to express words of genuine happiness. Envy, it seems, is a truly unattractive emotion.

Another close friend recently shared via email that she’s pregnant with her third child. I found myself unable to respond with congratulations. Of course, I can say I’m happy for her, and I harbor no ill will towards her or her unborn child. I want to envision her home filled with joy, but my good intentions fail to reach my heart—they freeze there, cold and unyielding. When lesser acquaintances post about their pregnancies online, my immediate thought often skews negative: “How nice for you.” As I walk my son home from school, I see young mothers with two kids and an obvious baby bump, and I can almost smell the contempt wafting from me, souring the air around us.

You might notice I mentioned having a son. It’s true, and I am incredibly fortunate for him. I recognize that I have a wonderful husband and an amazing six-year-old. On good days, I find solace in the simplicity of my family; on bad days, I feel an overwhelming sense of lack. The joy of my special boy, who has already grown into such a remarkable person, gets overshadowed by the label of autism that was assigned to him a couple of years ago. Meanwhile, my husband—who excels in fatherhood, cooking, cleaning, and possesses a certain charm—becomes the man who hasn’t given me a second child during these last two years of my fertility. When I dwell on my circumstances with negativity, it’s the goblin of self-pity that takes over. I find myself crying, declaring that I never want to hold another baby again, knowing I would only have to return it, as I wipe away angry tears while driving to work.

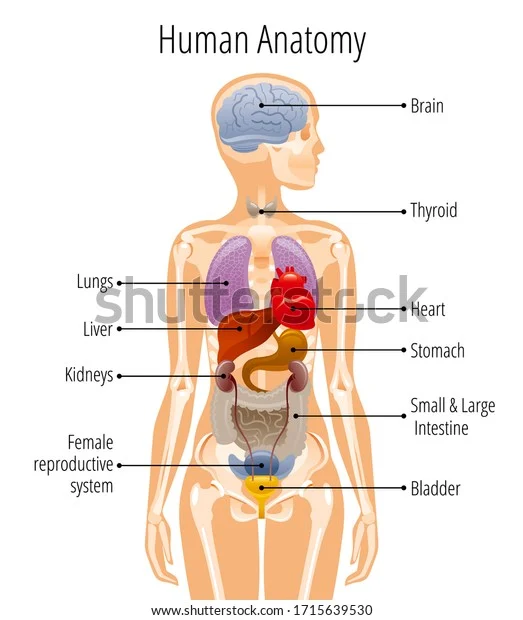

I’m consumed by thoughts of my dwindling fertility. I envision my ovaries like pomegranates, their seeds shedding early, leaving me with just a few feeble ones clinging to the walls of an almost empty chamber. It crosses my mind why someone couldn’t just give me one of those unwanted babies I read about in the news, lost by the time I hear their stories. I recall women who collect dolls designed to resemble newborns, their eyes closed, tiny fists curled. I once saw a woman on television who created these dolls as a way to cope with her own miscarriages and childlessness. I wonder how far I can wander into this fog of sadness and whether it’s possible to find my way back.

I find myself obsessing over the “what ifs.” I once met a poet who lived in a Los Angeles loft with panoramic windows, and I remember how Bryan Ferry’s music filled the air. I shared with her about my son, how at six he finally feels like a permanent presence in my life, and our struggles to conceive a second child. She offered comforting words: “We get what we get,” and “We all have our crosses to bear.” I mentioned my son’s preschool teacher, who finished her own thought with, “We get what we get, and we don’t get upset.” When I asked if she had children, she shared that she had a son who passed away. An unspoken weight hung between us. My apology lingers in the air, mingling with my fears.

I’ve never envied others for their material possessions or talents, but I desperately wanted a second child, and it seems that dream is slipping away. Meanwhile, friends younger than me continue to expand their families. When I see young women in grocery stores using WIC vouchers while pushing their children in carts, I can’t help but think, “Why am I funding this?” When lovely women with large families complain about exhaustion, my thoughts turn bitter: “Maybe you shouldn’t have had so many kids.” Age-related infertility has undoubtedly turned me into someone unrecognizable.

It’s likely there are women who would envy me for my son. I remember the bittersweet joy of his first latch, the pain in my gut as he pulled me back together. Overwhelmed with love, I cried as I preserved the tiny beanie and shirt he wore home from the hospital, now stored away with the remnants of my motherhood. A family member once told me how, during their years of trying and failing to conceive, his wife felt like strangling every friend who announced their pregnancy. They never even had one child. When we are denied our deepest desires while others seem to have them effortlessly, the absence can feel even more painful. I’m sure that when I shared my own pregnancy news—the one that resulted in my son—some acquaintance thought, “How nice for her.”

What if I opened up about my struggles? Acknowledging the darkness that overtakes me may be the first step towards healing. I’m reaching out, hoping to find connection. I’ve tried therapy, but left when my therapist offered cliched phrases that felt hollow. I’ve attempted to immerse myself in my writing, continually reminding myself to practice gratitude. I’ve even turned to antidepressants, which have helped lessen my tears and improve my sleep. I feel more equipped to navigate life, wrapped in a protective, chemically-induced layer. Yet, I wonder if the core of my being can ever return to sweetness, or if I’m destined to live with this new, sour heart—green and sharp as a lime.

This is not who I am, who I was, or who I want to be.

In Summary

Infertility can transform us in unexpected ways, leading to feelings of envy and bitterness that we may not recognize in ourselves. Despite the blessings we may have, such as loving partners and children, the longing for what we cannot achieve can overshadow our happiness. Through self-reflection and reaching out for help, we can begin to navigate these complex emotions and strive for healing.