In her best-selling memoir Glitter and Glue, Kelly Corrigan delves into the complex dynamics between mothers and daughters. The excerpt below highlights how her mother’s voice continues to echo in her mind, even as she embarks on her journey across the globe to Australia after finishing college.

I shouldn’t be in this situation. That’s the realization hitting me as I trail John Moore down the hallway of his suburban home in Australia. After our interview, I should have called to say it wasn’t a good fit. But I felt trapped. I needed funds, or I’d find myself back at my mother’s doorstep within a month, and wouldn’t that be music to her ears?

It’s her fault, I think, as I drop my backpack onto a single bed in a room with a skylight but no real windows. John Moore reassures me, “I hope this arrangement will work for you.” If she had just loaned me a little money…

This is not what I envisioned for myself. That’s the bitter pill I swallow when John tells me his kids are so excited about my arrival that they’ll be bouncing on my bed soon. “First nanny and all,” he says.

I’m a nanny, a freaking nanny.

For the record, I didn’t arrive in Australia and see an ad in the Sydney Morning Herald for “Recent Widower Seeking Live-in Nanny.” I was hoping for a bartending gig, or at least waitressing—good pay, plenty of fun, and guys everywhere.

My college roommate, Lisa, and I had been traveling for two months, depleting our funds. So when we hit downtown Sydney, we filled out applications at every restaurant and bar that seemed welcoming to Americans: Uncle Sam’s, Texas Barbecue, New York Grill. We followed up and waited. After a week, we expanded our search—surf shops, burger joints, cafes, pubs. Nobody wanted to hire us. We reached out to friends of friends, leaving messages asking for temp work. No one returned our calls. We scoured hostel bulletin boards, but no one was willing to let us work under the table. Three weeks later, we did what any self-respecting traveler would dread: we searched for nanny jobs, all of which were in suburban areas, where I’d meet zero boys and have zero big experiences.

I chose a wealthy family with an indoor pool and views of the Sydney Opera House, but Claire Thompson turned out to be a complete tyrant. After I grimaced at the thought of scrubbing her pool tiles and hesitated to help with her bridge tutoring flyers, I pointed out her ad specified “nanny,” not “nanny plus housecleaner plus personal assistant.” She told me I was her first American—she usually hired from Asia—and that I might be too “unionized.” Then she fired me.

Following that debacle, I interviewed with four more families. I told Cheerful Sarah in Chatswood that I was open to weekend babysitting, which sounded dreadful, and Fit Tom on Cove Lane that I was certified in CPR. It didn’t matter. No one wanted a nanny who could only stay for five months, so I returned to the newspaper, and the widower’s ad was still there.

John Moore was older than I expected for a man with a seven-year-old and a five-year-old. His mustache was graying, and his hairline had receded a bit. His shoulders were slumped, giving him the shape of a worn-out fridge. Overall, he seemed like someone who might participate in Civil War reenactments.

In a conversation that lasted less than an hour, he explained he was a flight attendant for Qantas and had recently lost his wife. It had been over six months since her passing, and he needed someone to help with the kids while he worked. He was fine with my short-term commitment, saying this arrangement would be a trial run for a more permanent solution. We shook hands, and just like that, I was hired. He didn’t even ask to see my passport. He was tired, and I was good enough for now.

The house was a ranch-style home, half-painted in an atrocious shade of orange—probably something like “Happy Face” or “Sunshine Delight”—leading me to wonder if he was color-blind or if his wife had handled those decisions. Half-opened paint cans lined the porch. There was no pattern to the painting, just messy splatters everywhere. The patches under the windows made the house look like it was crying.

In the living room, John’s widowhood was even more apparent. Crayon marks decorated the walls, and puzzle pieces littered the floor. The sofa’s slipcover was askew. On a side table, a plastic dinosaur lay toppled beside a framed school picture of a girl in plaid, pushed against a small treasure chest like the ones you get from a dentist or fast-food place. A piano bench overflowed with drawings on sheets that, as I got closer, I realized were music scores. “Tilt,” I hear my mother say, a reference to the message on pinball machines when players lose control. Some of her expressions are difficult to decipher. (I only recently learned that when she exclaims “Mikey!” after taking a bite of something delicious, she’s referencing an old Life cereal commercial.)

Once I unpacked my belongings, John’s son, Leo, bounded toward me on his tiptoes like a proud pony. He was skinny, with ears that pointed like those of a cartoon character.

“Keely!” he called, stretching my name out until it rhymed with “wheelie.” I barely met him during the interview, but that didn’t matter to him. We were friends already.

“Hi there!”

His smile was carefree, and his lips had a red crust from too much licking. I had lip balm in my pocket. I could start fixing that right away.

“Listen!” he exclaimed, as he leaped onto the piano and pounded out a chaotic yet joyful melody, spinning around to gauge my reaction, making me feel significant.

“Fantastic! Bravo! Do it again!” I clapped, encouraging him. He raised his hands dramatically in the air, pausing like a pelican ready to dive. “Go!” I urged.

He smashed his hands onto the keys again, creating a similar yet distinct tune.

“Brilliant. Pure—”

“LOUD NOISE!” shouted Mia, who had barely looked at me during our earlier encounter. “I’M TRYING TO WATCH MY SHOW!”

“I can play! Keely wants me to play!” Leo protested.

“Well, I don’t!” she retorted. “Dad!”

“Enough!” John interrupted, silencing both of them.

I peeked around the corner to make amends with Mia, who was slouched in a chair, clad in a plaid school uniform: a kilt and a white shirt, untucked. Her lips were pressed together, and her hands were tucked beneath her thighs. If she could make herself disappear into the chair’s crease, she would. She had a round face, freckles sprinkled across her cheeks, bright blue eyes, and thick sandy hair that shimmered with highlights a middle-aged woman would pay a fortune for.

“Hello,” I said.

“Hi,” she replied, barely moving her lips.

“So, you’re almost eight, right? Wow!” I commented. She shot me a look that seemed to say, Really? Is it that impressive? Her nail polish was chipped. I had a bottle in my bag. I could fix that too. “What grade are you in?”

She said nothing.

Things happen when you step outside your comfort zone. That’s my motto. I coined it during an Outward Bound trip after college.

During my solo adventure—three days and nights alone on a Florida beach with a tent, five gallons of water, an apple, an orange, and a first-aid kit—I made the most of what my eccentric counselor, Claire, dubbed “a unique opportunity to plan your life.”

After selecting a tent spot, dragging my water to a shaded area, and floating while singing “I Will Survive,” I pulled out my journal and charted my life in yearly and monthly increments. No way was I going to be just another apple rotting at the base of my mother’s tree. I was determined to experience life, to do meaningful things and learn important lessons. Seventy-two hours later, when Claire arrived in a boat, I had my major life choices sorted: work, grad school, relationships, moves, marriage, and even childbearing. I even set my peaceful death for the year 2057.

But despite all my ambitious planning, a year later I found myself unfulfilled. I was working a low-paying job at a non-profit in downtown Baltimore, living with my grandma, which meant that except for Tuesdays when I attended Weight Watchers, I spent my evenings eating hearty meals with her and my eccentric Uncle Frank. By eight o’clock, I was in my room—the same one where my great-great-aunt had passed away in a rocking chair—highlighting The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People while waiting for my next big move to become clear.

If I truly wanted to grow, I wouldn’t achieve that while living with my grandma, driving my unreliable Honda two miles to work, and clocking in for happy hour hoping some club lacrosse player would notice me. I needed to escape. I craved adventure. So, I found a round-the-world ticket deal in the back of The New York Times and convinced Lisa to join me. One year, seven countries—what an odyssey!

When I laid out my plans to my parents, my dad exclaimed, “Sweetheart, AMAZING!” in a tone that made me feel like I was taking a major step forward.

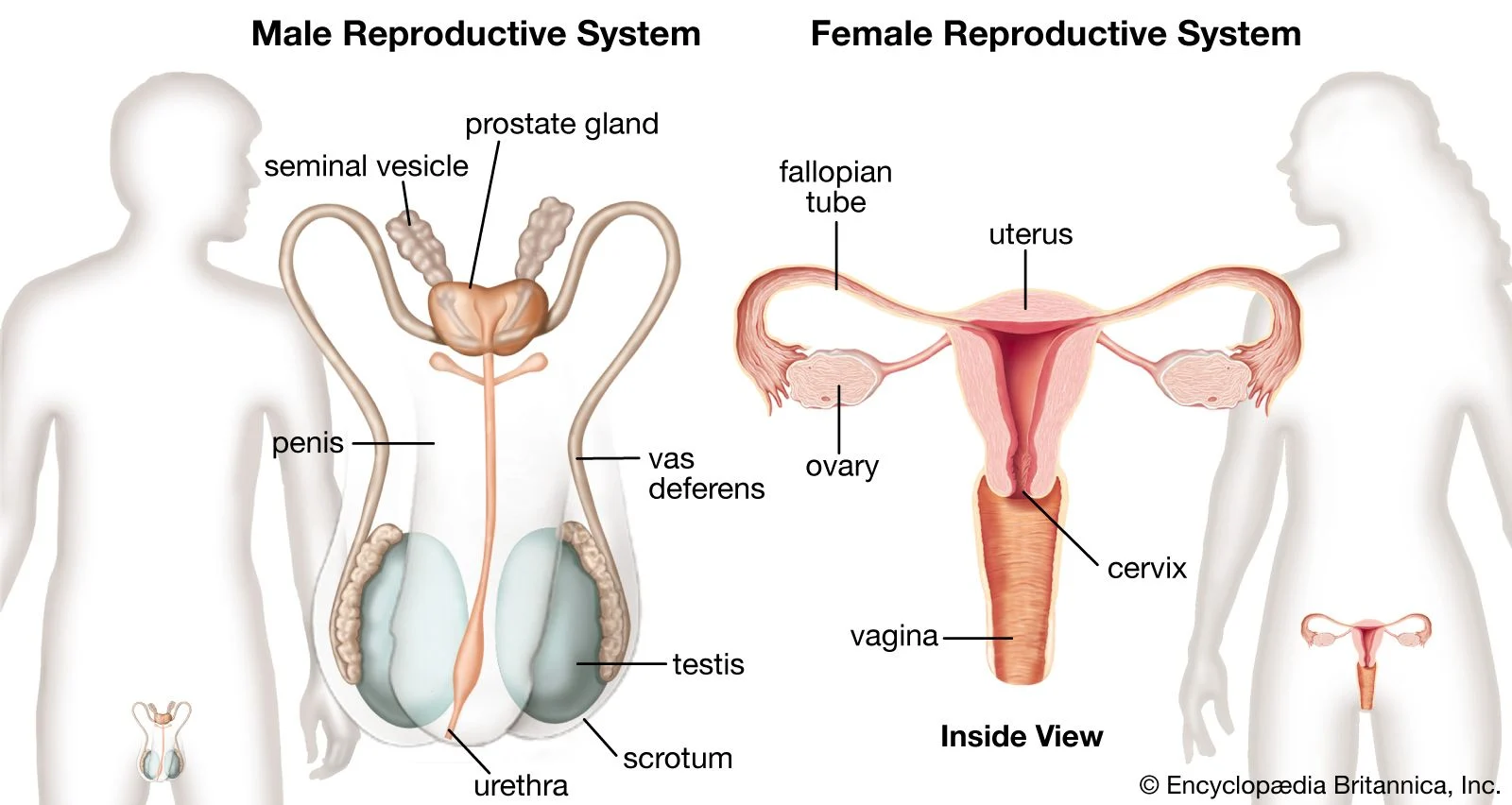

In the end, if you’re considering embarking on a journey of your own, whether it’s travel or starting a family, check out this insightful post on home insemination kits. Understanding the process can be crucial, and for further expertise, visit Intracervical Insemination, which offers valuable insights for aspiring parents. For more information on fertility and pregnancy, Cleveland Clinic’s IVF and Fertility Preservation podcast is also an excellent resource.

In summary, Kelly Corrigan’s Glitter and Glue invites readers into the intricate world of mother-daughter relationships, illuminated by Corrigan’s personal experiences. Her humorous yet poignant reflections remind us that life often takes unexpected turns, leading us to places we never imagined.